Fourth Circuit Says Victims Can Sue Feds for Background Check Failures

Earlier this year, I wrote about the so-called “Charleston loophole” that permits federally licensed firearms dealers to proceed with sale of a firearm if the background check hasn’t been resolved within three days. That “loophole” gained prominence after the massacre at Mother Emmanuel Church in Charleston, SC in 2015. The shooter’s purchase of the firearm used in the massacre was possible because the government examiner did not complete the background check—and determine that Roof was a prohibited purchaser—within three days. Last month, the Fourth Circuit ruled that the government’s failures that led to that fateful indecision were not immune from a negligence lawsuit filed by the victims.

The Charleston victims and their families brought a lawsuit against the federal government, arguing that certain failures during the background check review process constituted negligence. According to the victims, the government’s negligence delayed the processing and allowed Roof to purchase the firearm. The background check review process is conducted pursuant to the 1993 Brady Act, which mandates background checks for all sales by federal firearms licensees (like gun shops).

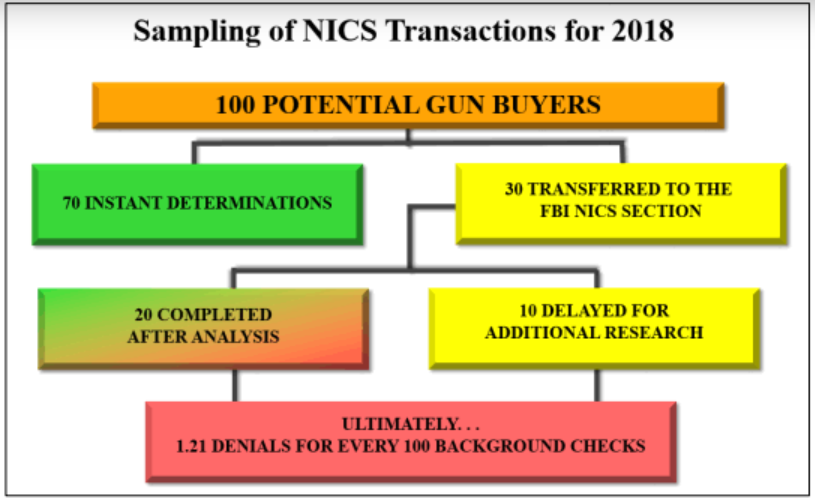

When a person walks into a gun store to buy a gun, the store contacts the FBI to run the background check. The FBI checks the purchaser against several databases to determine if the person is disqualified from possessing a gun. Normally, the response is immediate. (The system is called the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (“NICS”)). But sometimes the FBI tells the dealer the purchase will be delayed as the process continues. If, after three days, the results are still not back, the dealer may proceed with the sale at its discretion. The 2018 NICS Operation Report provides this overview of the government’s speed:

In 2018 alone, the ATF confirmed that dealers proceeded with nearly 4,000 sales to individuals who were ultimately determined to be prohibited possessors.

When the South Carolina dealer contacted the FBI for Roof’s background check, a series of missteps allowed the dealer to proceed with the sale after no resolution for more than three days. First, Roof had recently been arrested for drug possession, but the arresting authority was misidentified in the system. As a result, the government contacted the wrong agency to review the arrest report. Then, when it learned of the mistake, the FBI examiner contacted a different (also wrong) arresting agency that reported it had no relevant records. The government therefore did not get the actual report in time. At the same time, the actual arresting authority had submitted the report to the federal government, but to a database (the N-DEx database) that is not used for the background check system.

In the district court, the government claimed and the court held that (1) the Federal Tort Claims Act ("FTCA") and (2) the Brady Act barred recovery for negligent performance of a background check. But the Fourth Circuit disagreed. The FTCA generally allows suits against the government for torts except in specified circumstances. The Court found inapplicable the FTCA’s exception that forbids suits “based upon the exercise or performance or the failure to exercise or perform a discretionary function or duty on the part of a federal agency or an employee of the Government.” The Court held that the FBI’s internal policies for conducting background checks prescribed a specific set of tasks and therefore took away any discretion. Because the examiner did not follow those policies to contact the correct arresting agency, the FTCA’s discretionary-function exception did not bar the lawsuit. The Court rejected the separate argument that the FBI’s failure to include the N-DEx database within its search process for background checks could overcome the FTCA’s discretionary-function exception.

The Court similarly found inapplicable the Brady Act’s provision providing that “[n]either a local government nor an employee of the Federal Government or of any State or local government, responsible for providing information to the national instant criminal background check system shall be liable in an action at law for damages . . . for failure to prevent the sale or transfer of a firearm to a person whose receipt or possession of the firearm is unlawful under this section.” Because the victims sued the federal government—not any of its employees—the plain text of the Brady Act’s immunity provision meant it did not apply. What’s more, the examiners do not “provid[e] information to” the system, and so even a suit against them would not be barred by the Act.

The Court sent the case back to the district court to proceed past the initial stage. It may be difficult for the victims to establish all the elements of their case, but they are now allowed the opportunity to try.

The Fourth Circuit’s decision in Sanders echoes another recent decision allowing mass shooting victims to use tort law against someone other than the perpetrator. The Connecticut Supreme Court’s ruling that Sandy Hook victims could sue the manufacturer of the shooter’s gun has already prompted alarm in the gun-rights community. I've written previously about the Sandy Hook lawsuit here and here. Bushmaster’s cert petition seeking Supreme Court review of that decision is still pending. Perhaps we’ll see another cert petition soon asking for similar relief from this most recent tort-victim-friendly decision.