Analyzing Ramos Through a Second Amendment Lens

In a fractured decision on Monday in Ramos v. Louisiana, the Supreme Court held that (1) the Sixth Amendment requires unanimous jury verdicts, and (2) that standard applies equally to the states. Reaching this ruling required the Court to discard a 1972 case, Apodaca v. Oregon, in which another fractured Court had concluded that states could diverge from the unanimity requirement. Justice Gorsuch wrote the majority opinion in Ramos, and he was joined in at least part of that opinion by four other justices—Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kavanaugh. Justice Kavanaugh also wrote separately to expand on his views about stare decisis. Justice Thomas agreed with the result only. Justice Alito dissented, and he was joined by the Chief Justice and Justice Kagan.

In my view, there are some interesting parts of Ramos that both draw from and can inform Second Amendment jurisprudence. Here’s three observations.

- Justice Gorsuch does not like “interest balancing”

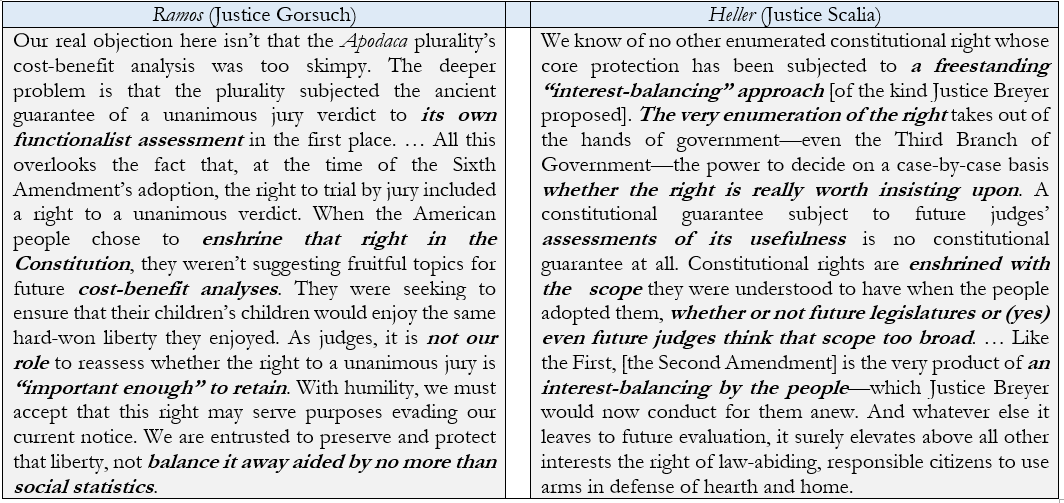

One of the reasons Justice Gorsuch provides for pushing aside Apodaca is that the plurality there engaged in a kind of “functionalist approach” that looked to the essential benefits of the jury right and the underlying purposes of that right. After highlighting some of what that approach looked like in Apodaca, Justice Gorsuch asked “Who can profess confidence in a breezy cost-benefit analysis like that?” He then made a broader jurisprudential point—in a portion of the opinion joined by the other four justices—that to me has some strong echoes with Justice Scalia’s rejection of interest balancing in Heller. Here are the two key passages side by side:

What’s remarkable to me is that Justice Breyer—who penned the Heller dissent expressly endorsing interest balancing—joined this part of the decision. In her separate concurrence in Ramos, Justice Sotomayor suggests she was not wholly on board with that part of Justice Gorsuch’s opinion, but she joined that part in full. As she writes, Apodaca was on shaky ground from the start, but “[t]hat was not because of the functionalist analysis of that Court’s plurality: Reasonable minds have disagreed over time—and continue to disagree—about the best mode of constitutional interpretation. That the plurality in Apodaca used different interpretive tools from the majority here is not a reason on its own to discard precedent.” To be sure, she might agree that functionalism should be discarded, and thus agree with Justice Gorsuch about the best way to approach constitutional interpretation, but simply think that that difference is not enough to reject Apodaca. But it’s still striking to see three of the more liberal justices join this part of Justice Gorsuch’s opinion—especially given that Justice Breyer wrote, and Justice Ginsburg joined, the dissenting opinion in Heller that Justice Scalia criticized in very similar terms. At the same time, because these justices agreed with the outcome, perhaps they thought this part inconsequential enough not to further divide the opinions in the case.

- The reliance interests of Americans matter in the stare decisis analysis

Another parallel with Heller is the majority’s rejection of precedent on the ground that the prior decision got the constitutional question wrong (or was at least read that way by succeeding judges). And in both cases, the majority invoked the reliance interests of ordinary Americans in its reasons to overturn precedent. As Justice Gorsuch says, “[i]n its valiant search for reliance interests, the dissent somehow misses maybe the most important one: the reliance interests of the American people.” For him, “the interest we all share in the preservation of our constitutionally promised liberties” is a reliance interest that must be taken into account.

In Heller, Justice Scalia similarly distinguished away United States v. Miller, in what the dissent considered to be a tacit overruling. Although Justice Scalia rejected that characterization, he did reckon with the argument that lower courts, at least, had read Miller in a way the dissent the suggested. Those courts’ “erroneous reliance upon an uncontested and virtually unreasoned case cannot nullify the reliance of millions of Americans (as our historical analysis has shown) upon the true meaning of the right to keep and bear arms.” Here too, ordinary Americans rely on accurate constitutional interpretation.

In both these contexts, it seems fair to ask: how are those reliance interests? Of course the American people have a strong interest in constitutional questions being rightly decided, but those aren’t interests they built up by relying on what the Court calls an incorrect opinion.

- Justice Kavanaugh’s thoughts on stare decisis could give a roadmap for advocates seeking to overturn Heller

Justice Kavanaugh’s thoughts on stare decisis are being closely watched, in part because he may be a pivotal vote to overturn Roe/Casey. But his thoughts on stare decisis might also prove informative for those advocates seeking to overturn Heller. Justice Kavanaugh provides three metrics to determine whether an opinion should be overruled.

- “First, is the prior decision not just wrong, but grievously or egregiously wrong?”

- “Second, has the prior decision caused significant negative jurisprudential or real-world consequences?”

- “Third, would overruling the prior decision unduly upset reliance interests?”

Of course, opinions are likely to differ on all three of those questions. But there’s at least a non-frivolous argument that determined advocates could make on each. As to the first question, Heller has faced mounting criticism from historians and linguists about the accuracy of its conclusions on original public meaning, as my colleague Darrell Miller has chronicled here.

As to the second question, there’s still a fierce empirical debate on the actual effect of gun laws, but one might point to laws struck down in Chicago and D.C. (other than the handgun bans) as negative real-world effects either because they lead to more gun injuries or because they take decisionmaking authority away from the political branches that (assuming point one above) should be making those decisions. Or one could point to the armed rallies and protests, inspired by the Second Amendment, that have the potential to chill First Amendment activity. Perhaps these sociological consequences are part of the inquiry into whether the decision proves administrable.

As to the third question, it’s not clear to me how to flesh out reliance interests on Heller. States by and large protect the arms right in their own constitutions, and a long and deep gun culture existed in the U.S. prior to 2008. There was certainly not a strong political appetite for prohibitory gun laws when states had the theoretical ability to pass them. Plus, there’s not a single person born after Heller was decided who can legally purchase a handgun, so it’s not as if there’s a large reliance interest there. On the other hand, both Ramos and Heller acknowledge that the views of Americans are a part of reliance. And in Casey too the Court took this interest into account: “The Constitution serves human values, and while the effect of reliance on Roe cannot be exactly measured, neither can the certain cost of overruling Roe for people who have ordered their thinking and living around that case be dismissed.”

Just to be clear, I don’t think Heller is going anywhere soon. But given what seems like a diminishing reluctance to overturn past decisions, it makes sense to look at what advocates would need to do to convince skeptical justices.