Parking Lot Laws: Their Content and Applicability

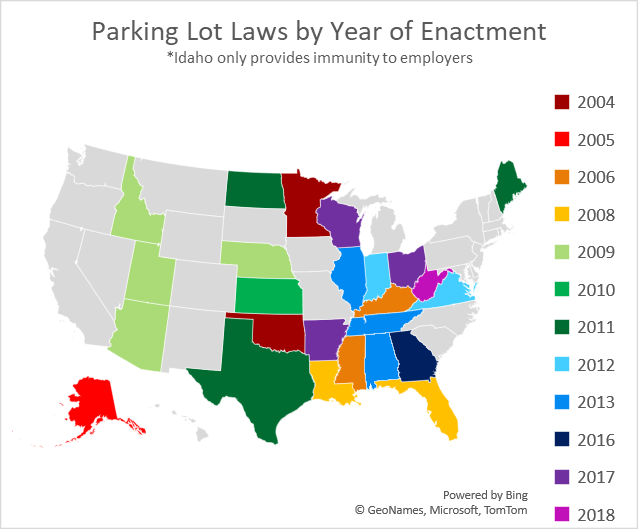

Last week’s blog on parking lot laws, state laws that prevent property owners or employers from banning firearms in parked vehicles in company parking lots, provided an overview of the history of these laws. Since Oklahoma enacted the first parking lot law in 2004, such laws have become widespread; nearly half the states have passed similar legislation, but the specifics of the laws vary from state to state. This post will describe the current landscape of these laws in the United States today: what they say, who they apply to, and what exceptions these various statutes provide.

Twenty-four states currently have some form of parking lot law in effect. One additional state, Idaho, does not have a parking lot law, but does explicitly grant immunity to employers who allow employees to store firearms in motor vehicles in the employers’ parking lots. The most recent state to enact a parking lot law was West Virginia in 2018, while the Wyoming and Iowa legislatures both recently considered parking lot laws.

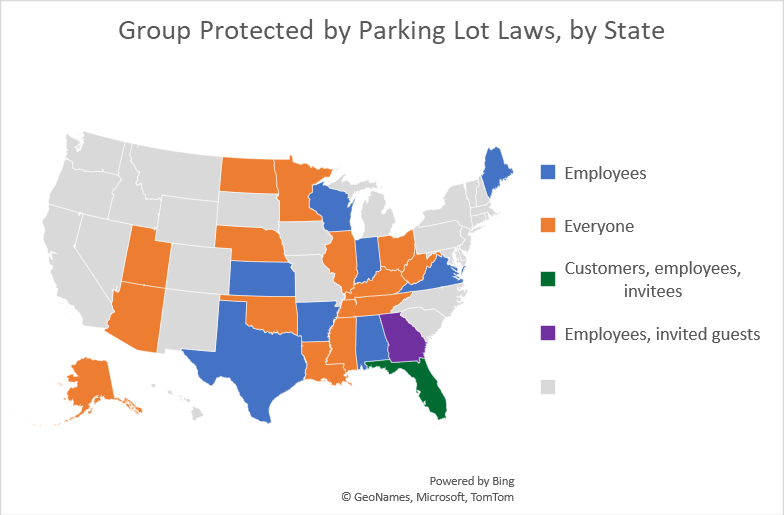

Of the twenty-four states with parking lot laws currently in effect, ten states regulate only the conduct of employers; one state, Virginia, regulates only “localities” (cities, counties, etc.) who act as employers; and thirteen states broadly regulate the conduct of groups such as property owners, business entities, operators of private establishments, or all individuals. Fourteen states’ parking lot laws prohibit bans that apply to all individuals (or all individuals who can legally possess and carry firearms), while eight protect only employees. Florida’s parking lot law protects customers, employees, and invitees, while Georgia’s protects employees and invited guests.

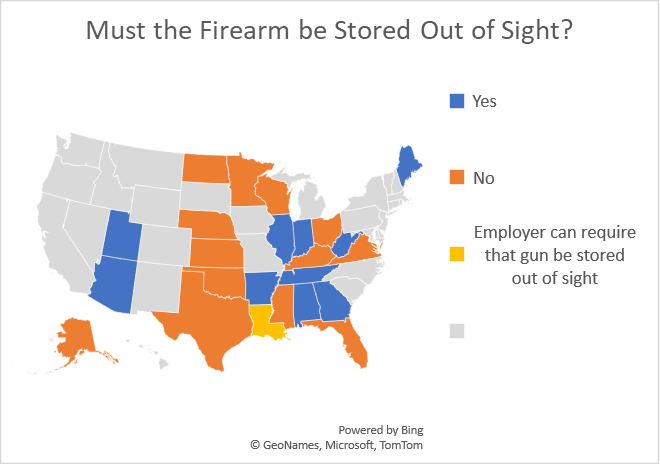

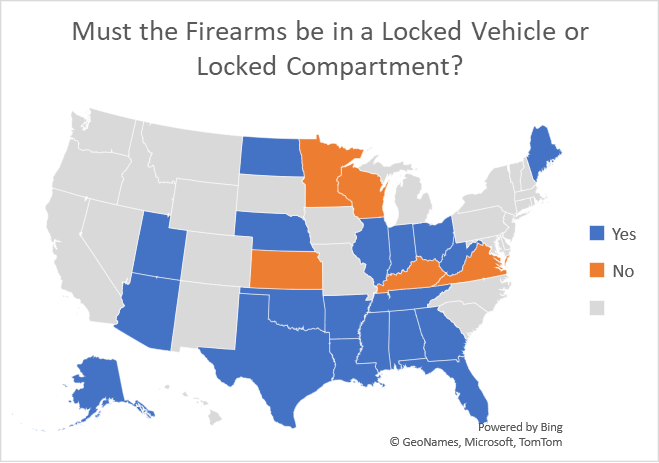

Ten states’ parking lot laws require that a firearm stored in a vehicle in a company parking lot be stored out of sight, while one more (Louisiana) states that an employer can implement a policy that the firearm be stored out of sight. Nineteen states require that the vehicle be locked or that the firearm be stored in a locked compartment.

Eighteen states grant employers or property owners immunity from liability for any injuries resulting from the storage of a firearm in a vehicle in a parking lot.

In addition to banning policies that prevent employees from storing guns in vehicles in parking lots, three states, Florida, North Dakota, and West Virginia, also prohibit inquiries about firearms that may be stored in vehicles. These states also prevent employers from searching employees’ vehicles for firearms; searches must be conducted by law enforcement officers. Additionally, instead of preventing employers from implementing policies that ban firearms in parking lots, Georgia’s parking lot law bans employers from searching employees’ vehicles, accomplishing a similar goal by removing the only reasonable means by which to enforce such a policy.

Seventeen states with parking lot laws, all but Arkansas, Illinois, Kansas, Minnesota, Ohio, Oklahoma, West Virginia, and Wisconsin, provide at least one exception under which an employer or property owner can prohibit the storage of firearms in a vehicle in a parking lot. The most common exceptions allow employers or property owners to ban the storage of firearms in vehicles owned or leased by an employer, or in areas where firearms are prohibited by federal law. Certain types of employers who “require[] a certain level of safety,” such as schools and child care centers, detention and correctional facilities, nuclear generating stations, employers who work with explosive or combustibles, employers who work in national defense, aerospace, or homeland security, and employers who work out of their homes, are often allowed to ban firearms from parking lots. Finally, three states, Arizona, Louisiana, and Utah, allow employers to ban firearms in a parking lot if they provide an alternative parking lot or storage area specifically for firearm storage.

While there is little litigation surrounding parking lot laws, in McIntyre v. Nissan North America, Inc., a case decided just a few weeks ago, an employee filed a wrongful discharge claim against his Mississippi employer after he was fired for keeping a gun in his vehicle in the company parking lot, which was surrounded by barbed wire, monitored by security cameras, and “secured with retractable drop arms.” The employee alleged a violation of Mississippi’s parking lot law, which states that employers “may not establish, maintain, or enforce any policy or rule that has the effect of prohibiting a person from transporting or storing a firearm in a locked vehicle in any parking lot, parking garage, or other designated parking area.” However, the law also contains an exception allowing employers to “prohibit an employee from transporting or storing a firearm in a vehicle in a parking lot . . . to which access is restricted or limited.” On appeal, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment for the employer, holding that the exception applied and the employee was not protected by the parking lot law because the employer’s parking lot was secured.

While parking lot laws are prevalent throughout the United States, McIntyre provides one example of the many ways in which these statutes vary from state to state. The simple idea behind parking lot laws—that employers cannot prevent employees from storing firearms in their vehicles—leaves plenty of room for nuance in practice.