Analyzing Maryland Extreme Risk Law Data

This past week, Joseph and I just finished another round of edits on our forthcoming Virginia Law Review article, Firearms, Extreme Risk, and Legal Design: “Red Flag” Laws and Due Process. Doing those edits, and working on another draft paper related to extreme risk laws, led me to dive more deeply into the statistics that are currently available. Maryland has some decent data, so I'm starting there in today's post.

Maryland’s recent Extreme Risk Protective Order (“ERPO”) law took effect in October 2018. Under that law, several groups of individuals may petition for an ERPO: (1) law enforcement officers, (2) family or household members and other specified relationships of similar nature, and (3) certain healthcare workers.

Most state frameworks have two kinds of ERPOs – temporary ones issued after an ex parte hearing and final ones entered after an adversary hearing. Maryland has three: (1) “interim” orders that a court commissioner enters, which can ordinarily only last 1-2 days, (2) “temporary” orders that a district court judge issues, which can last 7 days, and (3) “final” orders, which can last up to a year. Typically, interim orders only occur when the district court is not open, such as late at night or on weekends, when a court commissioner is all that’s available. Court commissioners cannot issue temporary orders, only interim ones. A district judge, as well as issuing temporary orders, is also permitted to proceed directly to a hearing for a final order if the respondent appears at the hearing and consents or if he had a prior interim order against him.

Because of this complicated structure, the Maryland data on petitions can be hard to put into perspective. A temporary order can occur without an interim order, and a final order can occur without a temporary order or interim order. The raw data comparing, for example, interim orders with final orders does therefore not give a complete measure of how often petitioners who seek or obtain an interim or temporary order secure a final one (and, thus, even less than usual what an "erroneous" ERPO would look like). But it can help identify trends and provide aggregate information.

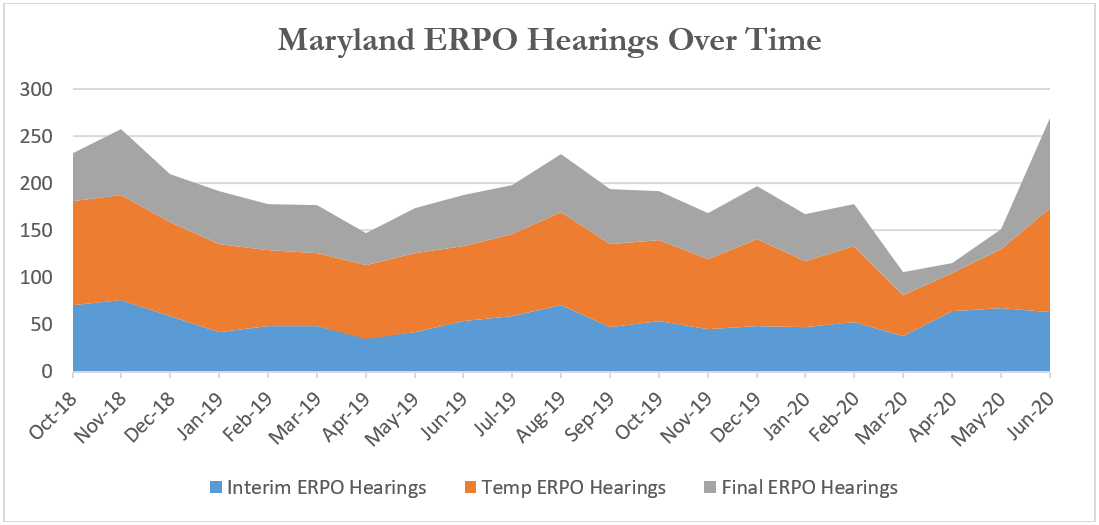

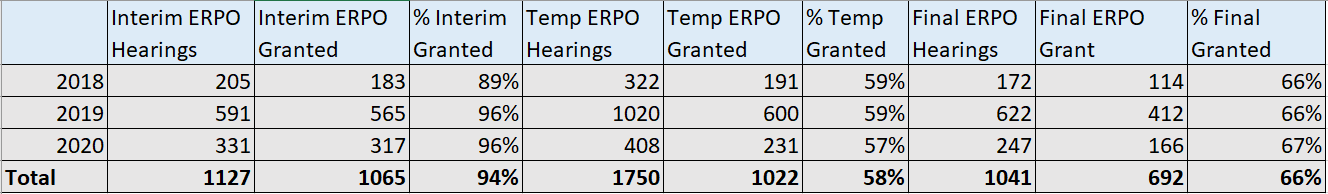

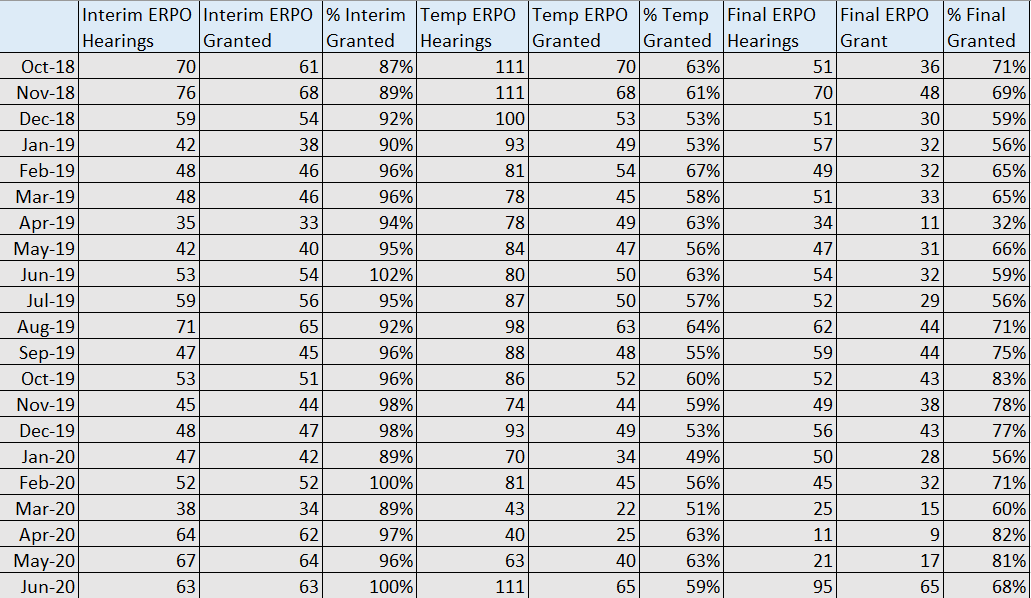

The state provides data by district and month; for the chart below, I aggregated this data for each year and calculated the percentages. Because there was no clear data on initial petition filings themselves—and what manner they were handled in (interim, temporary, or straight to final)—I break down the data by hearing type and order.

This data does not, to my eyes, support the notion that judges are rubber-stamping petitions. Temporary ERPOs are only issued after hearings (which can be ex parte but need not be) in about 3 of every 5 cases. To be sure, the way the data is recorded does not allow exact comparison; these are aggregate statistics on the number of hearings held that year and the number of granted petitions that year. That caveat is especially important for the monthly data below, with some months showing more granted petitions than hearings on petitions of that type.

Finally, ERPO hearings, which can be considered a fairly reliable proxy for petition filings, have remained pretty consistent over time. But there does seem to be a noticeable recent uptake, possibly as a result of added tensions related to Covid-19. Or perhaps the rise is the courts making up for the dip that occurred around the time of courthouse closures earlier this year.