Litigation Highlight: Michigan Appeals Court Upholds University of Michigan’s Campus Gun Ban

In a post last November, Jake summarized a remand order from the Michigan Supreme Court in Wade v. University of Michigan: a challenge to the university’s ban on campus possession of firearms with certain limited exceptions. The Michigan Supreme Court sent the case back to the appellate level last fall after Bruen, and Justice David Viviano concurred to articulate questions about how the Bruen test might apply in the campus context:

Even if certain restrictions were historically permitted on college campuses, another important question arises: are large modern campuses like the University of Michigan’s so dispersed and multifaceted that a total campus ban would now cover areas that historically would not have had any restrictions? In other words, are historical campuses the best analogy for the modern campus?

In short, Justice Viviano appeared to reject the notion that sensitive-places bans on college campuses present a straightforward inquiry and are constitutional under the umbrella of “schools.” Instead, he questioned whether “[m]any areas on campus, such as roadways, open areas, shopping districts, or restaurants, might not fit the ‘sensitive place’ model suggested by Heller—[and] may instead be more historically analogous to other locations that did not have gun restrictions.”

I believe Justice Viviano’s approach is both unnecessarily strict and inconsistent with other aspects of Bruen. On July 20, the Michigan Court of Appeals appeared to agree, affirming its prior ruling that the university’s ban is constitutional and dismissing the plaintiff’s claim for injunctive relief. After summarizing the parties’ supplemental post-Bruen briefs, the panel reviewed Bruen and its treatment of sensitive places. The decision found that the plaintiff’s proposed course of conduct—keeping and bearing a handgun on the University of Michigan campus—was protected by the Second Amendment. Moving on to the historical analogy step, the panel responded briefly to Justice Viviano’s concurrence in the remand order. Noting that Justice Viviano focused on 1791 as the relevant historical point, the panel consulted a 1773 dictionary to determine that the term “school” included universities at that time. The panel also found it relevant that: (1) a dictionary printed close in time to 2008, when Heller placed schools within its list of sensitive places where guns can be banned, similarly included “universities” within the term “school,” and (2) the law review article cited in Bruen’s discussion of sensitive places assumes that universities are schools.

The panel used these definitions and facts to determine that “the term ‘school’ was first used in Heller and was used broadly, without any limitations [. . . . and] in a colloquial sense.” The decision also noted other courts which have found universities to be “schools” and thus sensitive places under the Second Amendment. The panel rejected the plaintiff’s argument that some portions of the Michigan campus might be sensitive while others are not, and declined to interpret the Court’s endorsement of schools as sensitive places to merely establish a presumption of sensitivity that can be rebutted. Finding the university’s rules do not violate the Second Amendment, the panel held that “the trial court properly granted the University’s motion for summary disposition.”

Ultimately, I am not sure that parsing the word “school” by consulting historical dictionaries is all that persuasive as a method of judicial analysis. It’s also notable that the decision cites dictionary definitions of the word “school” from 1828, 1773, and 2003. But, because the rule at issue is a state university ordinance, I think there’s actually a strong argument that the historical inquiry should focus on 1868 (as I’ve discussed in prior posts here and here). The decision in Wade also illustrates yet another broad cleavage in how lower courts judges are applying Bruen. While Wade appears to take the Supreme Court’s dicta endorsing sensitive places bans in “schools” and work backwards to inquire into the semantic meaning of that term, other decisions—such as the recent opinion by District Judge Carlton Reeves in United States v. Bullock (which we covered here) and the Third Circuit's en banc decision in Range (which we covered here)—reject that course in challenges to the federal felon prohibitor. As Judge Reeves wrote, quoting a 1944 Supreme Court decision:

Treating dicta as binding violates the one doctrine more deeply rooted than any other in the process of constitutional adjudication: that we ought not to pass on questions of constitutionality unless such adjudication is unavoidable.

In general, I think Judge Reeves has the better of this argument (although, as he notes in Bullock, in some circuits lower courts may be bound by precedent to follow even dicta from the Supreme Court). The Supreme Court has not directly addressed the constitutionality of the felon-in-possession law, nor has it directly addressed the question of whether universities are sensitive places where guns can be prohibited. That does not necessarily mean the Michigan campus gun ban is unconstitutional, or that Heller’s endorsement of certain regulations is without import. Rather, it means that courts should not rely solely on dicta from a case where the Supreme Court did not confront or fully consider the specific legal question, without further analysis. Scholars have also persuasively argued that, “[i]nstead of simply isolating each location . . . judges should evaluate the reasons behind the sensitive places doctrine itself.”

Wade appears to implicate tricky historical questions including the prevalence of historical firearm bans on university campuses, whether those bans are representative considering the student population at the time, and why those bans were put in place. Jake’s prior post describes Founding era campus firearm restrictions at the University of North Carolina and the University of Virginia; the Virginia rule, which banned students from keeping or using weapons on campus, was passed by a board including James Madison and Thomas Jefferson in 1824. The Center’s Repository of Historical Gun Laws also contains a number of other campus gun restrictions from the 1700s and 1800s, available through this search, including a subsequent University of North Carolina regulation from 1838 and colonial-era laws restricting guns on campus at Harvard and Yale. While further historical research is needed into the justifications for these bans, the introductory sections or preambles of campus rules may provide some clues (courts might also look to where within the rules the firearms prohibitions are located, and to the intent of the surrounding provisions).

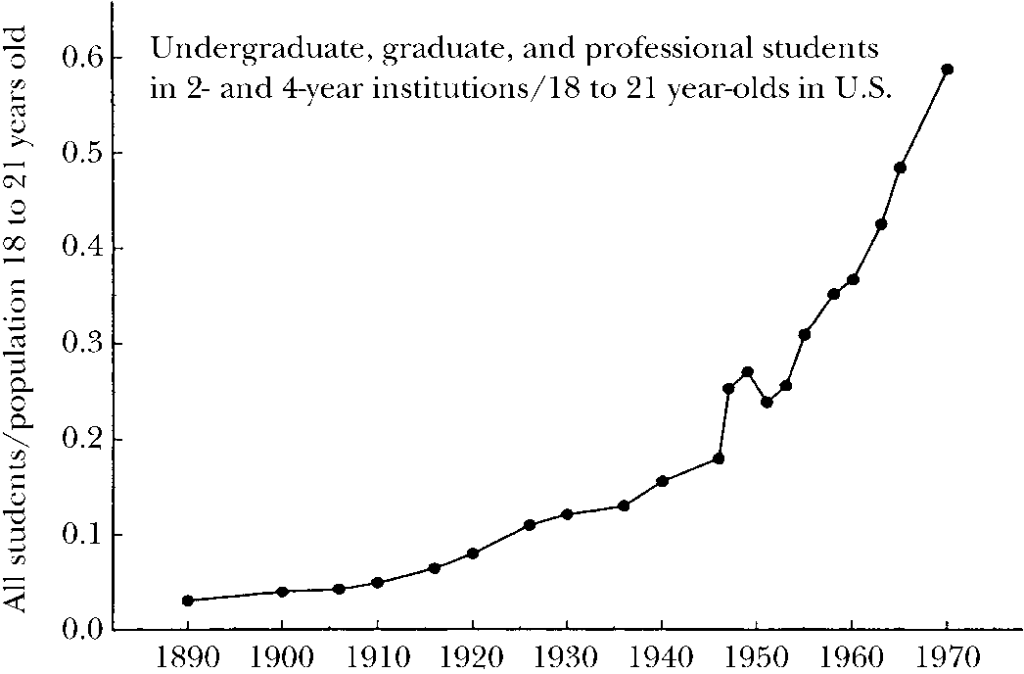

It is also notable that the early American history of higher education is largely one of private universities often associated with religious denominations. In particular, large public land-grant universities—which today often support massive student bodies and may create the perception that public college education is predominant—did not proliferate until the late 1800s after the passage of the Morrill Act. What’s more, an exceedingly small percentage of American young adults attended college up until the middle of the 20th century: while Founding era data is elusive, the number remained far below 10% of all 18 to 21 year olds as late as 1900 (see Figure 1 below). And both private and public colleges were almost entirely closed to women and minorities for much of American history.

Figure 1: College students as a percentage of 18-to-21-year-old U.S. population[1]

This historical background raises a number of complications with applying the Bruen test to campus gun prohibitions. First, it makes especially little sense in this context to treat the absence of regulation as proof of unconstitutionality when one considers the extremely limited role higher education played in American society during the relevant time period. One certainly wouldn’t expect to see legislative involvement, and even a small number of school rules might be evidence of a broad tradition given the possibility that only rules from a subset of prominent colleges have been preserved. Second, if judges limit themselves to legislation or public university rules, they may well be ascribing importance to an absence of regulation that is merely a consequence of the tendency toward private college education at the time (rather than any judgment about the right to keep and bear arms). I think this fact counsels strongly in favor of including private university rules within the Bruen analysis. Third, judges may be making decisions that disproportionately impact women based solely on historical laws that applied only to all-male colleges and which women had no input in developing (the same general point applies, with varying degrees of force, to different minority groups). If women and minorities were not attending college around the time of the Founding, or in 1868 for that matter, they surely also were not involved in considering or enacting regulations governing how guns could be kept and carried on college campuses. This is a broader problem with originalism, of course, but it’s especially salient in higher education where the legacy of exclusion is lengthy and entrenched.

As for Wade, the case may be appealed to the Michigan Supreme Court. The state’s high court flipped from majority-Republican to majority-Democrat in 2020. If the state supreme court hears the appeal, it seems fair to expect that Justice Viviano (at least) may reach a different conclusion about the university’s gun prohibition than the appellate panel.

[1] Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz, The Shaping of Higher Education: The Formative Years in the United States, 1890 to 1940, 13 Journal of Economic Perspectives 37, 41 (Winter 1999), available at https://scholar.harvard.edu/goldin/files/the_shaping_of_higher_education_the_formative_years_in_the_united_states_1890-1940.pdf.