The Second Amendment and the American Tradition of Firearms Prohibitions in Parks

This guest post does not necessarily represent the views of the Duke Center for Firearms Law.

Weapons regulations in “sensitive places,” or locations where governments can constitutionally prohibit the public carrying of firearms, constitute one of the most hotly contested areas of Second Amendment law since the Supreme Court decided New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen in 2022. After Bruen, many state and local governments that had previously enforced broader public carry regulations enacted new, location-based restrictions in response to Bruen’s holding that the Second Amendment protects a right to carry a gun in public. Challengers seeking to dismantle gun safety regulations in the wake of Bruen have targeted a variety of sensitive places restrictions, including prohibitions on carrying firearms and other weapons in bars, hospitals, mental health facilities, subways, zoos, beaches, and airports.

One sensitive place receiving particular attention is parks. And while prohibitions on guns in parks existed long before Bruen, an unprecedented number of challenges have been brought in state and federal courts across the country contesting the constitutionality of these restrictions under the Court’s new history-driven framework for Second Amendment claims. That framework—a standard focused on consistency with the Second Amendment’s text and the nation’s history of weapon regulation—led several courts to conclude that firearm prohibitions in parks violate the right to public carry under the Second Amendment. Those courts issued rulings preliminarily enjoining the enforcement of the respective park restrictions on the basis that the restrictions lacked sufficient historical analogues. And despite the Supreme Court’s more recent Second Amendment decision in United States v. Rahimi, in which the Court clarified the Bruen framework as one that allows for modern forms of firearm regulation connected to historically supported principles, challenges to restrictions on firearms in parks have persisted.

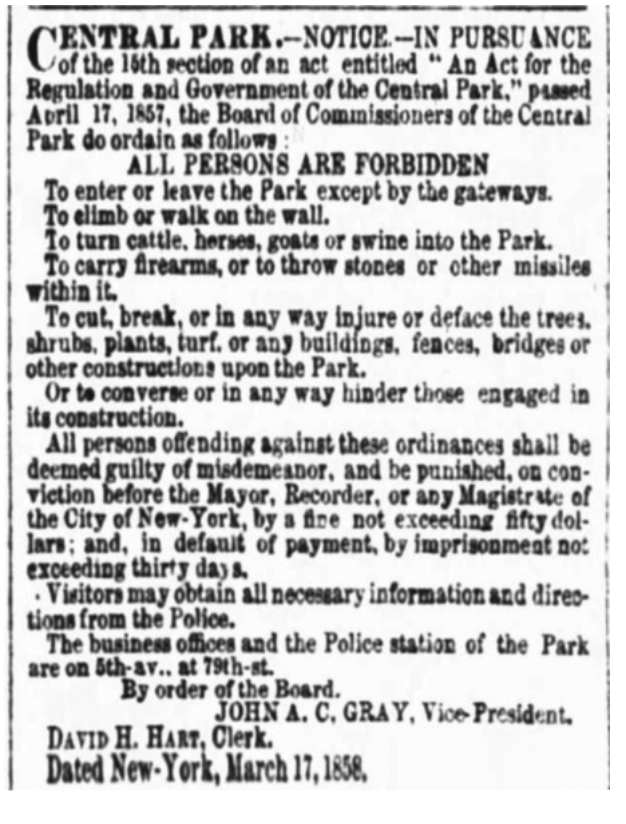

The decisions invalidating park laws have, in large part, been based on an incomplete historical record and a fundamental misunderstanding of that history’s relevance under the Bruen and Rahimi framework. We recently published an article in the Harvard Law and Policy Review that chronicles the history of the American parks movement and the history of regulations on guns in parks. We trace this history back from the emergence of modern public parks in the mid-nineteenth century through their proliferation during the decades that followed. When Central Park opened its gates in 1858, kickstarting the modern urban parks movement, a sign announcing a prohibition on carrying guns there quite literally greeted its first visitors. Cities across the country followed suit, building their own green urban oases modeled on Central Park.[1]

As cities created modern parks, they also enacted prohibitions on carrying guns in those parks. This trend began in the mid-nineteenth century and continued into the early twentieth century—at which point well over 100 cities and towns, as well as state and federal authorities, had adopted rules preventing the carrying of weapons in their newly constructed parks.

There does not appear to have been any serious controversy surrounding the passage of these prohibitions, including on constitutional grounds. The creation of urban parks was followed closely by a movement to preserve the natural beauty of areas outside cities and towns. American conservationists’ efforts to create wilderness parks slowly began to bear fruit in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As governments created new national parks and state parks, they also often prohibited the carrying of guns in those spaces.

Some have tried to argue that this near-universal adoption of public carry prohibitions in parks in the mid-nineteenth century is irrelevant under Bruen and Rahimi, claiming that governments did not similarly prohibit public carrying in earlier, supposedly park-like spaces. The most frequently cited example of an earlier, preexisting green space is the Boston Common. And while it is now clearly a modern park, our article unearths the Common’s early history, dating back to its establishment in the 1630s, and demonstrates that the Common of yore was quite a different space than it is today. Historically, the Boston Common, as its name suggests, was an American commons space: a collective, utilitarian space of production where cows grazed, militias mustered, and garbage was dumped. Although people sometimes visited for outdoor recreation, use of the Common for entertainment or leisure was merely incidental to its primary purposes. Recreation and leisurely enjoyment did not become central to the Common’s use until it was converted to a modern park in the mid-nineteenth century. Our article explores the distinctions between earlier colonial green spaces and modern parks in greater detail and explains the societal expectations that new, modern parks were to be enjoyed in ways very different from the commons and greens to which early Americans had grown accustomed.

Our article presents the history of the American parks movement alongside an unbroken record of gun prohibitions in parks. The history and the legal record of regulation we set out provide a more than sufficient historical basis to uphold similar laws today as they face new and unprecedented challenges to their constitutionality.

[1] Central Park, N.Y. Times (March 18, 1858).