An Interactive Database of Historical Public Carry Licensing Laws

This guest post does not necessarily represent the views of the Duke Center for Firearms Law.

In the decade and a half after District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), the biggest fight in Second Amendment law was over whether states could require applicants for public carry permits to show proper cause or a special need to carry guns in public. That issue was settled by the Supreme Court in New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen, which struck down New York’s “proper cause” licensing requirement. While Bruen decided the specific issue of need-based public carry licensing, a variety of challenges to licensing laws continue in the post-Bruen era.

In response to this ongoing litigation, we (Kellen and Mark) decided to write a law review article focused on the history of public carry licensing laws. To prepare for this project, we created a spreadsheet of the 116 licensing laws we are aware of that were enacted between 1866 and 1935, and broke those laws down across roughly 35 somewhat-overlapping variables. In this way, we were able to trace and highlight granular variation in the laws—including who issued licenses, who could apply for a license, what the standard was for issuance, which weapons specifically were licensed, who was exempt from licensing, how much licenses cost, what kinds of records were kept, and what penalties were incurred for carrying a weapon in violation of the statute.

We then got to work writing our article. After drafting about 15 pages, we came to the realization that while we had created a very interesting database, we were writing an extremely dull article. So we decided to simply publish our database. We brought Anna into the project, who cite checked and polished the database into the beautiful version that exists today. It is linked below as a “read only” Airtable. It is fully sortable and filterable. There are also some charts based on our findings available at this link for the more visual learners. We aim to update the database as we find new laws and ordinances, but we won’t be updating this blog post—so if you are reading this significantly after the publication date, you should double check the numbers. This spreadsheet has also not gone through a law journal cite check. That said, every entry was separately reviewed by at least two of us for accuracy. The original documents are all linked (some are accessible only through subscription services), and we would advise responsible lawyers and scholars to confirm the text of the laws at their source before directly citing them in a brief or article.

While the database is intended to cover all the generally applicable licensing laws that we are aware of, it certainly does not cover all laws that were enacted during the period. Finding these laws can be extremely difficult. Most historical licensing laws were enacted at the local level and are not available in the digital archives in which the majority of historical legal research takes place. We were able to locate some of these regulations in local newspapers, for example; but likely many more exist, if at all, in non-digitized form in local archives.

It would be nice if you cited us (maybe just this post) if you rely on the database extensively in a brief, article, or opinion, but it is not a big deal either way. We hope it is useful, or at least interesting.

Historical Licensing Laws Database

While our primary purpose is to simply share our database, we do have a few quick takeaways from the project.

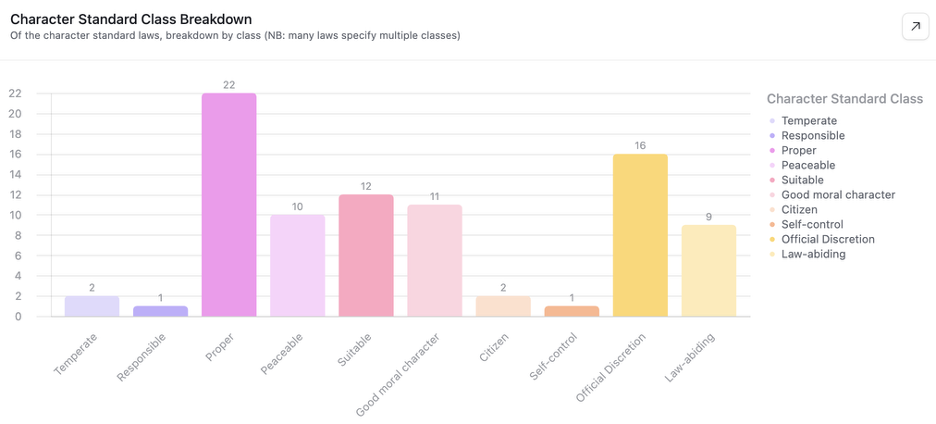

1. Conditioning licensing on an official’s views of an applicant’s character was very common.

Exactly half of the licensing laws in the spreadsheet contained some kind of express character standard. A chart showing the frequency of appearance of the different standards is above. These requirements were largely discretionary. Over and over, license issuers were asked to judge whether applicants had “good moral character,” whether they were “temperate,” “responsible” or “peaceable.” The most commonly occurring standard was simply that the issuing officer believed the applicant was a “proper” person to be issued a license to carry in public.

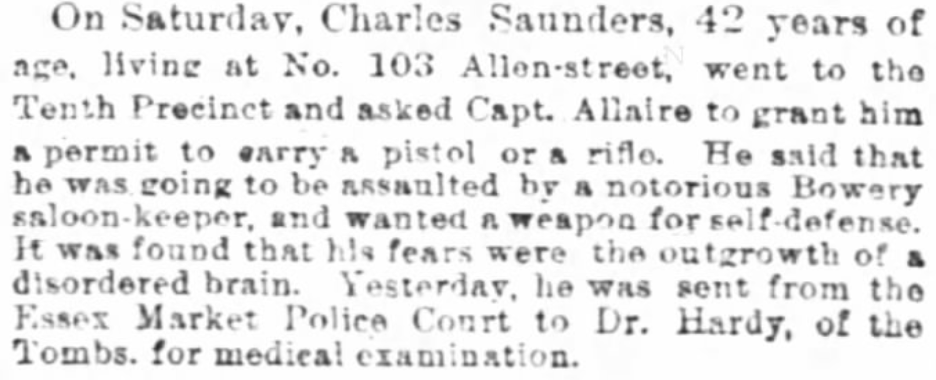

The text of the laws cannot tell us how these standards were actually implemented or applied. There was some reporting in local newspapers about license issuance. It seems that columnists were occasionally physically present when locals came to petition for carry licenses; their successes or failures often made it into the paper (more on this below). But these stories generally did not detail how issuers came to their conclusions, except in some cases where the scene of a license denial was particularly dramatic—as in this case, from New York in 1879:

There are also 58 licensing laws in our database that lacked any express character standard for issuance at all. Issuance of these licenses was entirely at the discretion of licensing authorities – “by special permission from the mayor,” “upon the recommendation in writing of the chief of police,” with “permission of the mayor or chief of police in writing,” or similar. Presumably, the licensing authorities were applying some sort of standard, and those standards likely would have looked something like the ones applied in jurisdictions with express language. Further historical research on this subject could help explain exactly how laws without written standards were applied.

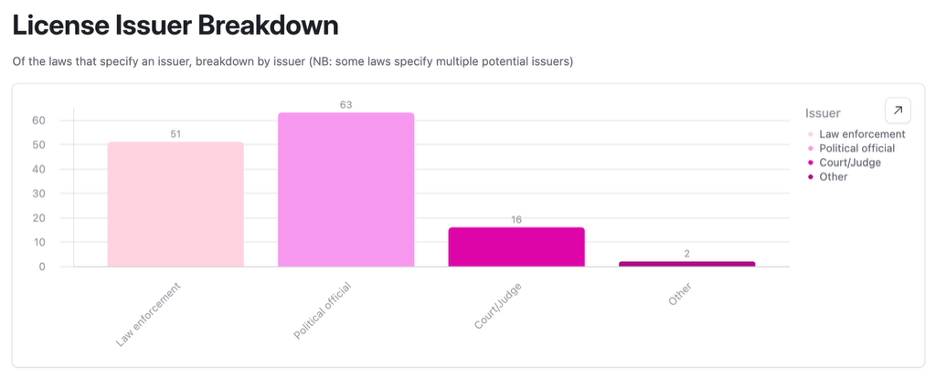

2. A majority of licenses were issued by political officials rather than law enforcement.

Although in the vast majority of states today local law enforcement is responsible for issuing carry permits, most of the jurisdictions in our historical database delegated that responsibility to elected officials. This power was usually vested in the mayor, but in many localities the city council or a similar body was responsible for issuing licenses.

This policy seems to reflect an older, small-d democratic impulse that kept ordinary citizens deeply involved in municipal governance in America. Local politicians were supposed to know and be accountable to their constituents. And while this was frequently more aspiration than reality, even into the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries it was certainly possible that in smaller towns the mayor would know many of their constituents by name, or at least by family. At a minimum, small-town officials would be aware of the most notorious local troublemakers. In larger municipalities, though, this system could backfire. When a Kansas City man named Joseph Carr was accused of a well-publicized shooting in 1890 and then found to have obtained a legally-issued permit for the weapon from the mayor himself, the mayor’s office offered the following (not particularly compelling) explanation for the oversight: “some gentleman whose name the mayor had forgotten came in and vouched for Carr and upon this voucher the permit was granted.”

It remains an open question why permitting regimes that concentrated power in the hands of mayors, aldermen, city councilors, and other high-level municipal officials persisted even into the twentieth century and even as the country urbanized. It is possible that wielding such power offered politicians an additional avenue for the granting or withholding of patronage or favor, for example. Additional research on historical licensing regimes could explain why so many localities for so long made licensing a political responsibility.

3. Licenses were not confidential

Newspaper reports on people being issued—or even just applying for!—concealed carry licenses were fairly common. Often, these included not just individuals’ names but also their occupations or even their addresses.

Sometimes stories about these requests would get picked up by press across the country. For example, a paper in Ogden, Utah, printed a short comment on the issuance of a license to a Chicago newspaperman, reporting that “Mr Michaelis, editor of the German Freie Presse, … applied for and received the necessary permit to carry concealed weapons. Either his articles or his readers must be of a pretty tough character.”

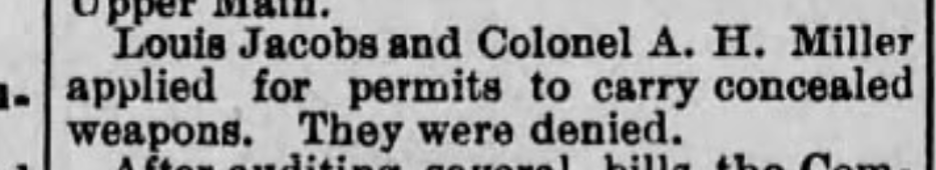

Newspapers sometimes reported denials of permits as well. Note the example below, in which two men, one a colonel, were refused a concealed carry permit:

While permits granted licensees the ability to carry concealed weapons in public, there was no reason for the licensees to expect their own identities to remain concealed. Indeed, West Virginia’s 1925 licensing law actually required applicants to notify their neighbors that they intended to apply for a permit by “first publish[ing] a notice in some newspaper, published in the county in which he resides, … his name, residence and occupation, and that on a certain day he will apply to the circuit court of his county for such state license[.]” Neighbors, likely better informed on their community members than circuit judges, would then have notice to provide the court with “evidence” that an undeserving applicant was not, in fact, “of good moral character[.]” Individual licensing procedures in this context were not just public knowledge, but often invited public participation.

4. Residency was not often required for a permit, but discretionary standards may have functionally limited permit issuance for non-residents.

We found 13 jurisdictions that expressly limited permit issuance to residents or people with businesses in the jurisdiction. That number likely vastly underestimates the regimes that functionally required residency—the discretionary licensing process would have made applying for a license difficult for those without clear ties to a jurisdiction. How could a mayor determine the “good moral character” of someone who was not even living in their town? It is also worth noting that we found no examples of inter-jurisdictional reciprocity, so a permit from one place was not a license to carry in another. Finally, of the 116 public carry restrictions we surveyed, only 14 of them had exceptions for individuals traveling through a jurisdiction.

5. While not always specific in their text, these laws were generally about licensing the carrying of firearms.

Some of the laws in our database enacted concealed carry bans on a wide variety of weapons (ranging from swords to stilettos to sandbags and beyond) while also creating permitting systems for a narrower list of arms (generally limited to pistols, revolvers and/or other handguns). Other regulations we found, though, were less specific in their text. In the town of Argentine, Kansas, for example, an 1882 law made it illegal to carry “in a concealed manner, any pistol, dirk, bowie-knife, revolver, slung-shot, billy, brass, lead or iron knuckles, or deadly weapon … provided that this Ordinance shall not be so construed as to prohibit officers of the law, while on duty, from being armed, or any citizen having a permit from the Mayor.” This rule, like many others in our database, did not stipulate which of the weapons the mayor was authorized to license.

It is almost certain, however, that the plain text of these laws alone does not paint the full picture of their function. Some of the weapons listed in the Argentine town ordinance above—like iron knuckles, for example—were not generally considered legitimate self-defense weapons, and the ordinance authors likely would not have expected that a mayor would issue any citizen a permit to wear them. Almost every story we have seen about actually-issued licenses during this era involves firearms. Rare exceptions may have existed, but even then, the licenses covered only other “normal” weapons. Such a possibility is hinted at in a 1911 Michigan statute that allowed residents to apply for permits to carry not just a “revolver” or “pistol” but also a “pocket-billy,” which referred to a type of very small club. Another point to consider on this front is that many of the more outlandish weapons regulated under these permitting laws were additionally criminalized by other state or local laws that emerged around the same time. The inclusion of slungshots—weapons that affixed a heavy weight to the end of a length of rope or cloth—in several of the licensing laws in our database is particularly illustrative; these items were widely banned in laws passed across the country in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. So, again, the text of these laws must be read in historical context, both in terms of the actual, real-world practice of licensing and in terms of the broader web of often-overlapping weapons regulations.

6. Licensing schemes sometimes operated beyond the bounds of the written laws.

In practice, licensing sometimes appears to have operated beyond the text of written laws. For example, in Cincinnati in 1876, the Enquirer reported that although Ohio had in place a state law banning concealed carry, and although “there is no provisions for permits of any kind, the Chief of Police may grant immunity from arrest to certain parties.” Functionally, then, Cincinnati operated under a permit system—but not one that would appear in any statute book.

A much more sinister example concerns the permits handed out by New Orleans’ police chief in spring 1866. He claimed when questioned that “he was aware [the permit scheme] was illegal, but that the exigencies of the occasion required it.” The occasion, in this case, was the ongoing attempt by white Louisianans to reestablish a white supremacist regime in the state after the Confederacy's surrender. The chief received a slap on the wrist for his engagement in off-the-books licensing; two short months later, former Confederates massacred Black freedpeople en masse in the New Orleans Massacre of 1866.

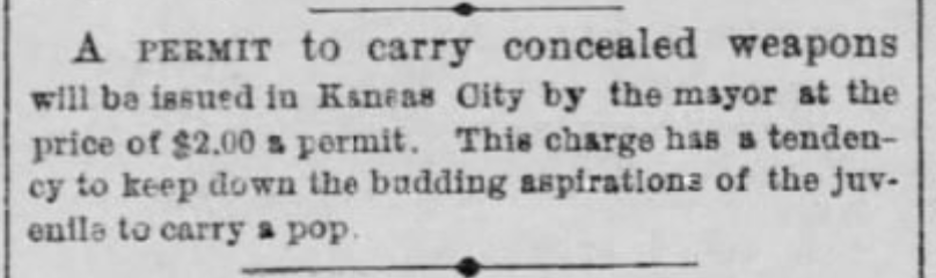

Another example of apparent deviation from text appears in Kansas City in 1882, where the mayor was reported to charge $2.00 for a permit to carry a concealed weapon. The permitting ordinance made no mention of a fee (and we are aware of no other law authorizing the fee):

These ad-hoc approaches to licensing were likely more common than historical research has yet revealed, especially because they could very easily pop in and out of existence without much documentation. Further research will need to be done to identify the full scope of the actual, on-the-ground practice of licensing regulation.

* * *

These are some of our takeaways from the database we’ve built and the historical research we did while building it. There’s so much more that can be learned from the Airtable, so we encourage you to take a peek.